Our website noigroup.com is getting one very big overhaul. In fact, we’re rubbing it out and starting again. With the old website being put out to pasture, we want to make sure that the years of collected content don’t get lost, so we will be re-posting some classic old NOI notes to ensure that they have a new digital home. It’s been an interesting process reading back over material from over a nearly ago!

We’re firing up the wayback machine once more and heading back to 2010 to look at one of the more vexed and certainly most discussed issues in pain – Central Sensitisation – with David Butler’s post Time for a closer embrace. What (seriously, just what) is it? Who ‘has’ it, can you has it? Should we try to talk about it with people experiencing ongoing pain? Is it a diagnosis?

Time for a closer embrace

Decades of denial

We have known about central sensitisation (CS) for at least 20 years, since Patrick Wall, Clifford Woolf and others published seminal papers suggesting that some pain and altered sensory states may be due to synaptic and membrane excitability changes in the central nervous system and not necessarily due to processes in tissues. This should have been a great relief to health professionals, but attempts to introduce the notion into rehabilitation, especially the manual therapy world (Butler 1994; Gifford and Butler 1997) were met with slow acceptance and often derision. I can recall introducing it in a conference in Scandinavia in the early 90s with the following speaker saying “well that’s well and good but we have to get on with the treatment”, and so the next session was on muscle stretching. “You are turning into a counsellor” was another comment. Many prominent physiotherapists and anatomists still deny the state and the current level of integration in most undergraduate and postgraduate programmes appears little more than lip service. Central sensitisation underpins modern biopsychosocial holistic management, yet we have a long way to go to integrate it. It deserves core curriculum status. A hot off the press review article by Clifford Woolf (2010) makes me believe that there may be a growing knowledge gap between science and practice.

Admitting that there is more to the story

For health practitioners to take on central sensitisation, they usually need to accept that the old peripheral story is not complete. A trigger point may have little to do with issues in the soft tissues, the palpably tender C2-3 nothing to do with processes around the joint, and the irritated gut only partly related to the gut, but are now known to be more due to a central nervous system which has lost the ability to “feature extract” from input and defaults quickly to a pain construction. The pathophysiology of this state is now well described. See Latremoliere (2009) and Woolf (2010) for updates. Of course this can be a challenge – many successful practitioners have a lot of clinical mileage at stake and large investments in continuing education. While many readers of these notes will have embraced it, most of the rehabilitation community is yet to integrate it.

A word from a big picture expert

Gordon Waddell (1998) summed it up nicely when defending modern holistic biopsychosocialism “it is all very well to say that we use science and mechanical treatment within a holistic framework, but it is too easy for that framework to dissolve in the starry mists of idealism. We all agree in principle that we should treat people and not spines, but then in daily practice we get on with the

business of mechanics.”

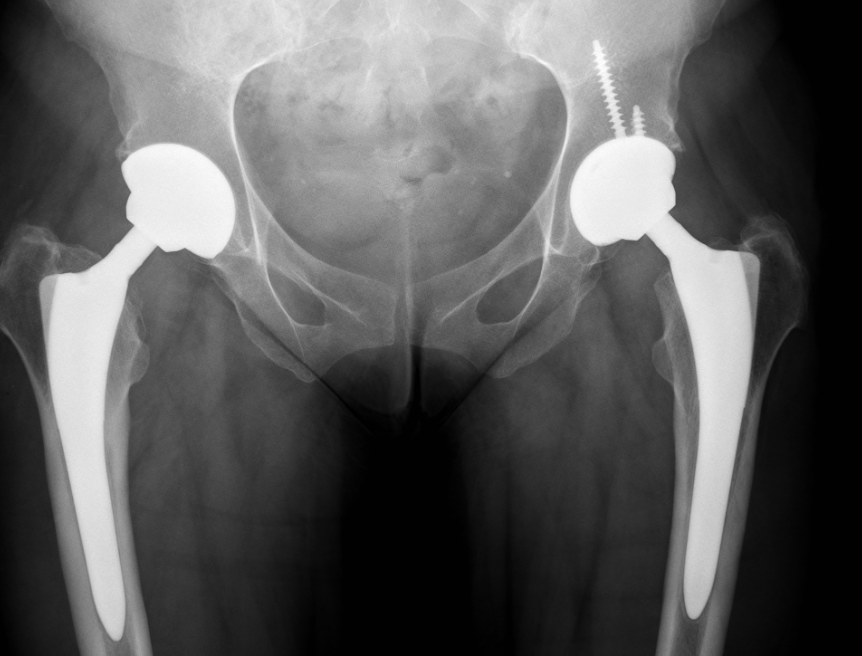

“But what about chronic knee OA and OA hips that respond to hip replacement”

The hard core biomedicalists often bring this out as evidence of the tissue base of chronic pain. Of course, these are peripheral diseases which are often amenable to peripherally directed management. But even here, the degree of pain does not match radiological finding or degree of inflammation, suggesting a central mechanism as well (Bradley, Kersch et al. 2004). In OA knees (Arendt-Nielsen, Nie et al. 2010) and OA hips, there is impaired central inhibitory controls. This key feature of central sensitisation will improve with hip replacement (Kosek and Ordeberg 2000). This and other data summarized by Woolf (2010) strongly suggests central sensitisation should be a consideration in all acute and chronic pain states.

Bums into gear

This NOInotes is unashamedly all about getting readers to update, reconsider and read the Woolf update – here you can read all about CS in rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, TMJ disorders, fibromyalgia, headache, miscellaneous musculoskeletal disorders, post surgical pain, irritable bowel syndrome etc. etc.

Central sensitisation is treatable, though currently predominantly by medication. The NNT (number of people need to treat to get one with 50% pain relief) in fibromyalgia for a drug like pregabelin is around 6 (Russell 2006). This simply reinforces the fact that the conservative forces of management need to get their bums into gear, review current paradigms and get CS evidence based management strategies including neuroscience education (Butler and Moseley 2003), graded activity and exercise, imagery, mindfulness, and appropriate manual therapies out there and heard. Central sensitisation is so liberating in the clinic – the relentless and often disappointing searches for sources of nociception in the clinic becomes less important and it supports the critical notion that functional restoration can processed even in the presence of pain.

And there is a little bit of muted satisfaction seeing the research emerge which supports the importance of central sensitisation in all acute and chronic pain states.

-David Butler, 2010

Has the pendulum swung too far?

After ‘decades of denial’ CS seems to be everywhere in the pain literature now – as a mechanism, a phenomenon, a diagnosis, and in some cases a ‘catch-all’ for any persistent pain. No one can seem to agree what it is and the insidious conflation of nociception of pain is evident as soon as you start reading. Take for instance this from a recent Special Issue on Central Sensitisation in the Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research:

“Central sensitization refers to the amplification of pain by central nervous system mechanisms… Features of central sensitization have been identified in nearly all chronic pain conditions, and it is considered the primary underlying cause of pain in conditions such as fibromyalgia” (emphasis added)

You keep using that phrase ‘central sensitisation’…

The now ubiquitous use of central sensitisation has prompted some researchers to ask questions about what exactly the phrase means and how it should be applied. The general consensus seems to be that there is no consensus, with some calling for a diminution of the scope of central sensitisation – back to the basic science itself. In an excellent commentary from 2018, van den Broeke et al (sorry, paywalled) make the following points:

“In sum, we conclude that

(a) the term CS, as defined by the IASP, refers to changes in nociceptive neurons only and therefore cannot be applied to enhanced responses to stimuli other than nociceptive and/or pain;

(b) the evidence for CS in widespread pain (other than secondary hyperalgesia) and many other conditions is scarce to absent;

(c) at this moment, CS is a descriptive label for the explanandum rather than an explanation and, as such, suffers the risk of being a circular explanation; and

(d) the explanatory role of learning and cognitive and emotional factors should be considered as potential mechanisms for the wide range of phenomena that are currently interpreted as evidence for CS. We therefore propose to reserve the term CS for the phenomenon related to its discovery: the increased excitability of spinal nociceptive neurons triggered by peripheral nociceptive input” (emphasis added)

What to make of this? Pedantic semantics? Perhaps the answer can be found with a deep dive into the literature…

The CS rabbit hole will get you every time

Go on, we dare you… just start reading a few papers on central sensitisation, then a few more, maybe just a few more… We’ll see you on the other side (maybe)! It’s a fascinatingly deep rabbit hole to get lost down, but a rabbit hole none the less with more questions than answers and multiple conflicting definitions and ideas. If nothing else though, you’ll come out knowing your heterosynaptic from your homosynaptic potentiation, and a whole lot more about NMDA receptors. Want to read some blogs to get you started? A couple of excellent posts here and here – both with excellent comment sections to lose yourself in!

As ever, back to the clinical encounter

So where does the idea of central sensitisation fit in the clinic? At NOI we’ve been contacted by a number of people who have been told that they have Central Sensitisation Pain. Some have been quite worried and distressed by the “diagnosis”, however at least one was quite reassured – finally having been given a reason for their pain; a phrase, a concept – something, anything – to ground their experience.

Are we as clinicians still in denial? Or have we become addicted to an overly-simplistic conceptual category in which to lump everyone with ongoing pain? Your clinical mileage will vary, and we’d love to hear about it below.

-NOI Group

PS. This was going to be a relatively short post, but the CS rabbit hole got us too!

2019 NOI Courses Australia and New Zealand

AUCKLAND 15 – 17 MARCH 2019 | EP+GMI *FULL*

AUCKLAND 23 – 24 MARCH 2019 | MONIS *FULL*

ADELAIDE 6 – 7 APRIL 2019 | MONIS *Full*

HOBART 3 – 5 MAY | EP+ GMI *Last Places*

KINGSCLIFF 14-16 JUNE | EP+GMI

MELBOURNE 5-7 JULY | EP+GMI

NOOSA 2-4 August | EP+GMI

SYDNEY | 23-25 August | EP+GMI *NEW LISTING*

ALBURY WODONGA | 18 – 20 OCTOBER | EP+ GMI

BRISBANE | 15 – 17 November | EP3 – Moseley, butler & Vlaeyan

References for the original NOInote ‘Time for a closer embrace’ above

Arendt-Nielsen, L., H. Nie, et al. (2010).:”Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis.” Pain 149: 573-581.

Bradley, L. A., B. C. Kersch, et al. (2004).”Lessons from fibromyalgia : abnormal pain sensitivity in knee osteoarthritis” Novartis Found Symp 260: 258-270.

Butler, D. S. and L. S. Moseley (2003). Explain Pain. Adelaide, Noigroup Publications.

Butler, D. S. (1994). The upper limb tension test revisited. Physical Therapy of the Cervical and Thoracic Spines. R. Grant. New York, Churchill Livingstone.

Gifford, L. and D. Butler (1997). “The integration of pain sciences into clinical practice.” The Journal of Hand Therapy 10: 86-95.

Kosek, E. and G. Ordeberg (2000).”Lack of pressure pain modulation by hetereoptic noxious conditioning stimulation in patietnns with painful osteoarthritis before but not following surgical pain relief.” Pain 88: 69-78.

Latremoliere, A. and C. J. Woolf (2009).”Central Sensitization: a generation of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity.” The Journal of Pain 10: 895-926.

Russell, I. J. (2006).”Fibromyalgia syndrome: Approach to management” Bull Rheum Dis 45: 1-4.

Waddell, G. (1998). The Back Pain Revolution. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone.

Woolf, C. J. (2010).”Central sensitization: Implications of the diagnosis and treatment of pain.” Pain (in press)

Physiotherapy industry is now like fitness industry… “Paradigm shifts” every month, to sell or convine patients or ourselves we’re developping new tools, the good ones this time (all were bad, and now definitively we know the “truth about”, we’re debunking the myths, etc. etc. Problem: the Dunning-Kruger effect seems to be highly active in physio community. Competences are not evolving with the speed of the increase in volume of literature (rate of pubkications). Physios are not well prepared enough to play with some concepts. So, a lot actually thinks they’re doing “psycho-logy”, others are fascinated by neo-phrenology (without knowing the basics of neurology, imaging, etc, sometimes), others persuaded they manage the biopsychosocial model with ease (just ask if a person is happy). Lack of culture sometimes, of basic formation… Why do physios hate so much their profesion that they now want to be psychos, personal trainers (PT want to be physios on the other side…). We invoke “evidence” (to give us identity or strengthen opinions, associated with often the need of social media marketing… Who really read papers ? Who knows really how to interpret them ? Who has the epistemological tools ? Time ? 5% of physios ? Who reads beyond the comments of gourous ? The guys in the labs ? And ? This is a crisis of identity, with the good, the bad and the ugly sides. Thanks for your job.

Then the correct term is “central sensitization of nociception”.

Clinical relevance

Although there are some clinical clues that suggest the central nervous system of a person may be sensitised, it is not possible to objectively measure the process in intact animals (including humans). Such clues include increased response (including pain) to a non-noxious stimulus to the skin in the area of the pain complaint, applied either statically (e.g. blunt pin) or dynamically (e.g. brush), pain in response to non-noxious passive movement of the relevant part of the body, pain in response to deep pressure in the area of pain, and worsening of pain after clinical examination of the area of pain.

The next question to address is that of underlying neurophysiological mechanisms.

As a unifying hypothesis, could neuroinflammation be the mechanism?

What is neuroinflammation?

Neuroinflammation is difficult to define precisely but broadly speaking it refers to a particular response demonstrated by imaging within the central nervous system (brain and/or spinal cord).

As occurs in tissues elsewhere within the body, the process of neuroinflammation is characterised by the release of small molecules called cytokines from resident glial cells (microglia and astrocytes), as well as from cells lining brain blood vessels (endothelial cells), and from immune cells living outside of the central nervous system.

Cytokines can be thought of as signals used for communication between cells within the nervous system, and between these cells and other cells in the body [DiSabato et al. 2016].

It is important to know that there are degrees of neuroinflammation, some of which are beneficial and others that can cause harm [Milligan & Watkins 2009].

Beneficial effects

Neuroinflammation is critically important in early brain development, in memory and learning, in the “pruning” of unneeded synapses (unwanted connections between nerve cells), and removing waste products of brain cell turnover.

The glial cells (glia means “glue”) are briefly activated whenever a bodily infection or injury occurs and this activation triggers physiological and behavioural responses that are essential to recovery. Collectively these responses are known as “cytokine-mediated sickness behaviour”. Perceived psychological stressors are also capable of activating the glia, associated with identical responses.

The features of sickness behaviour (or response) in animals (including humans) include fever, loss of appetite, listlessness, fatigue, decreased activity, and reduced social interaction. Other manifestations are disturbed sleep, disturbances in mood and memory, and increased sensitivity to non-tissue damaging stimuli (e.g. light touch). In humans, widespread pain and deep tissue tenderness can also be reported.

When properly controlled and regulated, sickness behaviour is said to be beneficial in that it reallocates the body’s resources to fight infection or to limit tissue injury and to then promote its repair (but this is a teleological argument). The duration of glial activation and exposure of nerve cells to cytokines is usually short and the response completely resolves.

Importantly, these responses are found throughout the animal kingdom and have been conserved by evolution [Lyon et al. 2011].

Harmful effects

When neuroinflammation is unchecked, it can be damaging when it occurs in the following conditions: infections of the central nervous system, stroke, and in neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. The damage to nerve cells in these conditions is caused directly by cytokines and various other products released by the glia.

How is neuroinflammation detected in the CNS?

Evidence of neuroinflammation can be indirectly visualised by using a scanning technique known as Positron Emission Tomography (PET). Through the use of a radioactive tracer, a translocator (“moves to another place”) protein by the name of TSPO has been identified within cells, where it sits on the membrane of specialized structures known as mitochondria. These tiny structures play a major role in the production of cellular energy by serving as “batteries” that power various cell functions.

TSPO is always present in low concentrations in the healthy brain but the glia produce increased amounts following brain injury, in neurodegenerative conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic and lateral sclerosis, and infection [Crawshaw & Robertson 2017]. It is therefore a useful biological marker for these conditions, as well as in patients presenting with “chronic low back pain” and “chronic widespread pain” (aka fibromyalgia) [Albrecht et al. 2019].

Where to from here?

If neuroinflammation is indeed the underlying mechanism, it may then be possible to define “chronic pain” as another disease state characterized by an objectively demonstrable biomarker.

References:

Albrecht DJ, Forsberg A, Sandström A, et al. Brain glial activation in fibromyalgia – A multi-site positron emission tomography investigation. Brain, Behavior and Immunity 2019; 75: 72-83. Doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.09.018

Crawshaw AA, Robertson NP. The role of TSPO PET in assessing neuroinflammation. J Neurol 2017; 264:1825–1827. DOI 10.1007/s00415-017-8565-1

DiSabato D, Quan N, Godbout JP. Neuroinflammation: the devil is in the details. J Neurochem 2016; 139(suppl2): 136-153. Doi:10.1111/jnc.13607.

Lyon P, Cohen M, Quintner J. An evolutionary stress-response hypothesis for chronic widespread pain (fibromyalgia syndrome). Pain Med 2011; 12: 1167-1178.

Milligan ED, Watkins LR. Pathological and protective roles of glia in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009; 10(1): 23-36. doi:10.1038/nrn2533

This topic is addressed in Explain Pain Supercharged, as follows…

Hansson 2014 made the argument that central sensitisation should only refer to physiological events at the dorsal horn as originally described by Woolf. Hansson did not think there was enough evidence for clinicians to use the term central sensitisation to explain clinical presentations like fibromyalgia etc

( https://insights.ovid.com/pubmed?pmid=25067835 )

Thankfully, Woolf himself replied with a contradictory view that central sensitisation is an appropriate recommendation for persistent pain states. He also explains that his group first coined the phrase central sensitisation when studying the dorsal horn but, in his opinion, central sensitisation can occur in any parts of the central nervous system that contribute to pain hypersensitivity

( https://insights.ovid.com/pubmed?pmid=25083929 )

I was quite relieved to read Woolf’s response as he voices a sensible, clinically-relevant approach to central sensitisation. If the term was Dorsal Horn sensitisation then it would be inappropriate to use it as an explanation for a wide range of clinical presentations. However, calling it central sensitisation means it is an umbrella term that can apply to the sensitising process for pain production that occur anywhere in the central nervous system. This includes brain areas for thoughts, emotions, sympathetic, endocrine and immune responses etc.

I think it is understandable that some pain researchers feel a bit protective of the term considering that it started it’s life as a quite specific neuro-physiological phrase, but I think we should all be able to share the phrase with an understanding that it can have slightly different meanings depending on the context in which it is used.

It is definitely an interesting debate!

Tom