Our colleagues at the Persistent Pain Research Group, University of South Australia, drive collaborative research aimed at advancing the understanding and treatment of persistent pain. By working involving consumers, their impactful studies can span from discovery to implementation science. Their research focuses on identifying the factors underlying persistent pain and developing novel brain-based interventions based on this knowledge. We welcome you here to read about, and possibly participate in one of their latest studies: Understanding the role of persistent pain in daily decision-making.

Your comments, as always, are welcome.

– Noigroup

What’s pain for?

Acute pain is an unpleasant, multisensory experience typically caused by inflammation or tissue damage. Although unpleasant, those everyday aches and pains (such as headaches, toothaches or stomach pain) are necessary parts of our existence: They tell us something wrong is happening in our bodies, and remind us to take a break and take care of ourselves. For example, when we sprain an ankle, pain informs us to take some rest to help our tissues heal and prevent further damage.

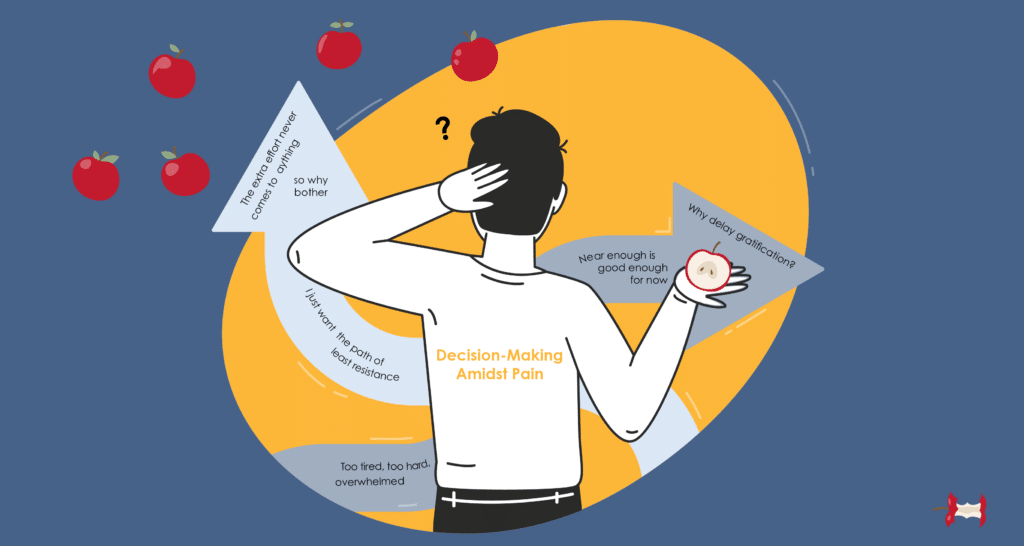

Yet, sometimes, pain persists even when its initial cause is long gone. The unpleasant experience becomes chronic and is no longer informative in the same way that acute pain is. When pain persists even after the tissue has healed, avoiding physical activity may have short-term benefits including experiencing less pain while exercising, or feeling less tired. Yet, avoiding physical activity may be detrimental in the long run, leading to lower fitness, higher body weight, and even more pain. In fact, in many persistent pain conditions engaging in exercise and other activities shows strong evidence for relieving pain and regaining function (Ambrose and Golightly 2015).

There’s a problem, though. These physical activity strategies require short-term effort (i.e., ‘costs’) and typically have delayed benefits that only come to fruition in the longer term. For example, engaging in exercise programs often initially increases pain levels. Yet sustained engagement in exercise reduces pain over time (often requiring 3 or more months (Lee and Kang 2016)).

The cost/benefit tradeoff

We know that both the delay in receiving a reward and the effort required to get it affect how we value different outcomes (Kirby, Petry, and Bickel 1999; Mitchell 2004): We generally prefer to receive something now, without having to work for it, than to receive a slightly bigger reward that we have to either wait for or put an effort into getting. However, the rate at which an individual devalues larger delayed or effortful rewards is highly unique to that individual. Put another way, some people will perceive that even a short delay or a small amount of effort to receive a benefit is not ‘worth it’, whereas others will feel that a greater delay in benefit or a decent bit of effort will still be ‘worth it’ for that reward. Generally speaking, showing more willingness to wait/work for a larger reward is related to many health and general life advantages, such as longer life expectancy, better health, lower body-mass index etc (Volkow and Baler 2015).

In those experiencing chronic pain, willingness to tolerate delay and effort may also be essential for treatment adherence and outcomes. It is also possible that like other aspects of pain where our systems can become over-protective, decisions relating to effort might be over-protective. Thus, understanding more about how decision-making occurs when rewards/benefits are delayed or effortful is important because it can also help inform what sort of treatment we should provide.

Understanding decisions in persistent pain

To tackle this issue, in a recent study (Herman and Stanton 2022), we recruited a large group of individuals who experienced long-term pain, defined as pain lasting for at least the past three months (N = 391). We also had a group of participants without a history of persistent pain (N = 263). Participants were asked to make a series of hypothetical choices between two options: A smaller reward available immediately, or a larger reward available after a delay. For example, “Would you prefer to receive $5 now or $10 after a week?”. They also made similar choices for effort, for example, “Would you prefer to receive $5 without any effort or $10 after climbing 8 flights of stairs?”. By giving many different options, we could determine where, for each person, a certain delay or amount of effort switches over from ‘worth it’ to ‘not worth it’.

So, what did we find? People who were experiencing long-term pain were less likely to choose rewards that were delayed or that required effort than people without pain. That is, they required more reward for a certain delay or effort to be ‘worth it’. Importantly, these differences between groups remained even when we controlled for several demographical and pain-related factors, showing that these differences are robust.

While these findings are interesting, there is more that we need to know! First, it’s not clear if these differences in decision-making for delayed and effortful rewards are pre-existing or whether they develop once people have chronic pain (e.g., we learn that greater effort truly isn’t worth it). Further, we aren’t sure if the same group differences would exist if the relative ‘difficulty’ of effort was individualised to each person – what is low effort for those without pain can be high effort for those with pain. We are now testing what happens when we individualise effort to the person. If group differences still exist, this would provide support for the idea that these decisions may be ‘over-protective’ in people who have pain.

Nevertheless, our findings show the importance of considering attitudes towards delay and effort in people with chronic pain. Low levels of engagement with exercise interventions in people with pain can sometimes be inappropriately interpreted as merely low motivation when instead, our results suggest that engagement may be influenced by changes in decision-making. If our work supports that decision-making might be over-protective in people with pain, this raises the possibility of new interventions that aim to target decision-making itself. For example, previous research has shown that imagining oneself in the future makes people more likely to choose delayed rewards (Peters and Büchel 2010).

Participate in the study

If you would like to help us understand better the ways persistent pain may affect the way we make decisions, consider participating in this (confidential) online study. We are seeking two groups of participants:

-

individuals who are diagnosed with a persistent pain condition (lasting for a minimum of the past 3 months). We are looking for individuals with a variety of conditions (e.g., fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, lower back pain, painful knee osteoarthritis etc).

-

individuals who were never diagnosed with persistent pain (pain that lasted for 3 months or longer) and who do not currently have pain.

You need to be 18 years or older, fluent in English and have no diagnosis of cognitive impairment (e.g., Alzheimer’s or dementia) in order to participate. Your participation will provide wider benefits to the community by providing important information on the relationship between long-term pain and daily decision-making. This may also help develop new interventions in the future.

Thank you for reading.

– Aleksandra Herman

Visiting Associate Professor

University of South Australia

Persistent Pain Research Group

Hopwood Centre for Neurobiology

Lifelong Health Theme

SAHMRI

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the European Commission (EC), Horizon Europe Framework Programme (MSCA) no 101059716.

Banner image

Created using various elements taken from a licenced version of Envato Elements.

References

Ambrose, Kirsten R., and Yvonne M. Golightly. 2015. “Physical Exercise as Non-Pharmacological Treatment of Chronic Pain: Why and When.” Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology 29 (1): 120–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.022.

Kirby, K. N., N. M. Petry, and W. K. Bickel. 1999. “Heroin Addicts Have Higher Discount Rates for Delayed Rewards than Non-Drug-Using Controls.” Journal of Experimental Psychology. General 128 (1): 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.128.1.78.

Lee, Jung-Seok, and Suh-Jung Kang. 2016. “The Effects of Strength Exercise and Walking on Lumbar Function, Pain Level, and Body Composition in Chronic Back Pain Patients.” Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation 12 (5): 463–70. https://doi.org/10.12965/jer.1632650.325.

Mitchell, Suzanne H. 2004. “Effects of Short-Term Nicotine Deprivation on Decision-Making: Delay, Uncertainty and Effort Discounting.” Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco 6 (5): 819–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14622200412331296002.

Peters, Jan, and Christian Büchel. 2010. “Episodic Future Thinking Reduces Reward Delay Discounting through an Enhancement of Prefrontal-Mediotemporal Interactions.” Neuron 66 (1): 138–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.026.

Volkow, Nora D., and Ruben D. Baler. 2015. “NOW vs LATER Brain Circuits: Implications for Obesity and Addiction.” Trends in Neurosciences 38 (6): 345–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2015.04.002.

Does the study also include decisions that participants have determined for themselves hold meaning for them to engage with? For instance, if someone experiences incredible persistent pain a reward of $10 for climbing stairs may not be sufficiently motivating weighed up against all the other daily tasks that need decisions on whether to engage with. If it were $10 every time the stairs were climbed to celebrate laying the foundation to build themselves up to something they really want to be able to do, would that affect the decision making process? Also interested in knowing if anyone involved in the study design experiences persistent pain? I see a lot of usefulness in having lived experience guiding the design of these kinds of studies.

It would be interesting to know how much of this type of decision-making (delayed benefit is not worth the effort ) was pre-existing and maybe contributed to the chronic pain condition.