Stumbled on this quite by accident, but it is a rather nice potted history of some thinking about pain. The History of Biopsychosocial Pain – A tale of Gladiators, War, Papal Doctrine and a Wrestler, by Dr Harriet Wordsworth. The essay was a previous winner of The Anaesthesia History Prize awarded by The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Selected excerpts below (all the words in italics).

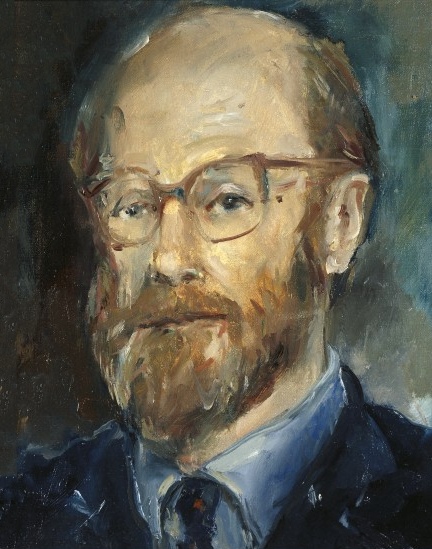

George Engel and the origin (?) of the biopsychosocial model of illness

The ancient Greeks

Galen and the Romans

The Dark Ages, ‘poena’ and the Pope

The Enlightenment

Von Frey and the Victorians

The Great War

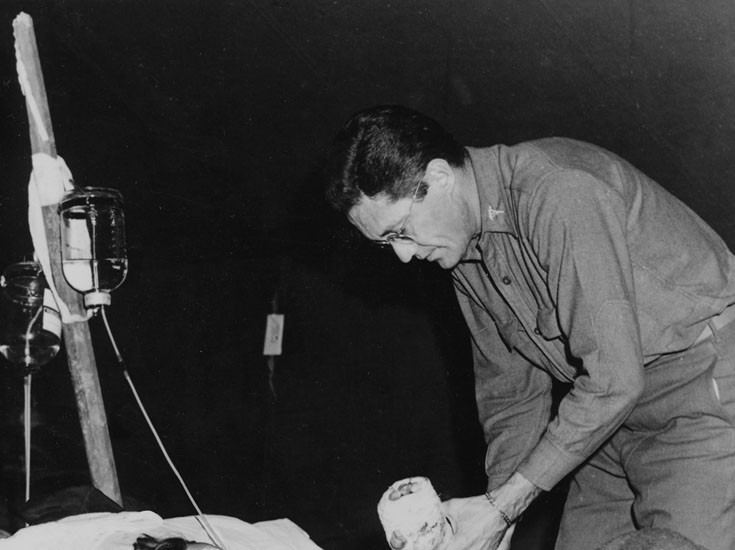

World War II and the post war era

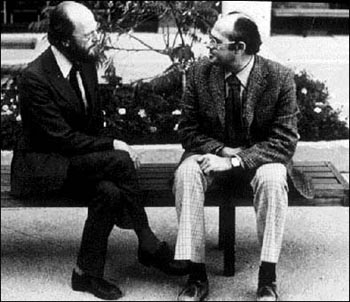

Melzack, Wall and the Gate

The swinging ’60s

The ’70s, the founding of IASP, and Wall’s ‘need state’

The ’80s and onwards

Because it’s you and me, we’re history

It’s a great essay from Dr Wordsworth (sorry, couldn’t find a link to a professional page or bio), available in full for anyone to read here. Perhaps the abiding lesson of history is that at any point in time, we are not as clever/novel/forward thinking as we’d like to think we are. If the biopsychosocial model was a person, it might be a Kardashian – nothing new, better known for its curvy figure and picture than for any substance, in and out of fashion, good to name-drop in the right circles, has had way too much of the same things written about it over and over, is talked about by many, but is understood by few (talk about burying the lede…). This doesn’t take away from Dr Wordsworth great essay, or Engel’s original idea, but it does suggest that knowing a little history may be humbling and have some benefits – Plato was on to the ‘placebo effect’ thousands of years ago; Galen’s philosophical thinking made him a better physician; strongly held, dogmatic beliefs (religious or otherwise) can harm people; by carefully listening to, and observing soldiers with terrible injuries Beecher was aware of the tenuous link between tissue damage and pain over 70 years ago; Bonica was advocating multidisciplinary approaches to pain in the ’50s but was ignored; Wall and Melzack’s gate control theory was never just a theory of dorsal horn ‘gating’; and very few people to this day understand Wall’s idea of a need state. And there’s so much more – of course.

Back to the future – ‘Understanding Pain in 2025’

My sincere thanks here must go to Mick Thacker for giving his 2015 Louis Gifford Lecture talk the title Understanding Pain in 2025: Top Down before Bottom Up! and allowing a nice way to wrap this post up on an upswing, going back a few years to peer into the future. Discussing perhaps the most truly biopsychosocial (in Engel’s original formulation) model of pain around, Louis Gifford’s Mature Organism Model, Mick explores his own, embodied, formulation of the MOM, introduces the idea of Predictive Processing (PP), and discusses the work he is doing with one of the PP aficionados, Andy Clark, to take a PP approach to pain. Mick highlights along the way Louis’ prescient understanding of where pain science is heading, evident in his top down before bottom up maxim. Click on the image below for a link to the video. It’s long – but put aside the time, you’ll be smarter for having watched it.

Brilliant, Tim. Thanks for the great read, the added pictures, the laugh 2/3 through, and the link to Micks brilliant work as well! Cheers

Thanks Keith, glad you enjoyed reading it!

Tim, is it possible that the ancient theological beliefs of mediaeval Christianity in relation to women (about the Fall and Original Sin) have persisted to this very day and are playing a part in our societal stigmatisation (and punishment) of women experiencing pain that cannot be medically explained? As yet, I have not located any substantial evidence to support this rather radical opinion but wonder what others who have read your blogs are thinking.

Thanks John, it would seem a logical and defensible argument to me. In more recent times the Victorian (and earlier) notion of ‘hysteria’ may be a link in a causal chain? I believe that the American Psychiatric Association only ceased using the term in 1952.

Tim

Tim, I cannot defend it with any solid evidence, which is why I raised it in this forum.

The two great neuroses of the late 19th and early 20th century were “hysteria” and “neurasthenia”.

The former lives on buried under the label “somatoform disorders” and the latter under that of “fibromyalgia”.

Extricating fibromyalgia from this connotation of being a psychological disorder is proving to be exceedingly difficult.

The swinging ’60’s: “Insurance companies in the States were accumulating more and more chronic pain patients and thought that a psychological intervention, where the patient was encouraged to be responsible for the management of their own symptoms, provided a cheap answer to their prayers. This meant that psychological therapies at this time often had financial backing to carry out large trials. However, they had not appreciated the cost of implementing such services and, consequently, the cost passed onto the insurance companies themselves.”

What is happening to these patients in the more enlightened 2010’s? How are compensable insurers managing these long-term claims and containing the costs thereof?

Are there any contributors to this discussion?

Tim, let me be even more provocative.

As I see the current situation, health care professionals are inextricably enmeshed in systems of personal injury compensation that can only result in these patients being treated as expendable commodities.

Certain medical professionals willingly provide insurers with medico-legal reports that deny the reality of persistent (chronic) pain conditions, and many physiotherapists in private practice are providing these patients with copious amounts of useless and outdated treatment.

The evidence provided to the Royal Commission related to the insurance sector has lifted the lid on the bad behaviour of insurance companies.

Does such behaviour extend to their pivotal roles in workers’ compensation insurance?

In my opinion, it would be worth having some feedback from health professionals who follow this blog, as it remains to be seen whether the vaunted “Pain Revolution” is going to improve this situation.

It becomes an issue of “causation”, and whether the issues identified are due to conscious actions of “bad actors”, or something more unconscious and more about the inevitable consequences of how our institutions developed and hence the “systematic processes” we have thus inherited. From a Marxist perspective it boils down to greed and exploitation on the part of bad actors…perhaps which accounts for some of the variation within health care but I think it goes deeper. From Weberist perspective (Max Weber, the other great sociologist of the 19th C), it boils down to a deep and potentially fatlisitic existence angst that underlies the human condition itself. I think the deeper issues relate to bigger questions that can only be addressed through rexamination of foundational ideas like the basis of a viable “social contract” and many of the issues raised in game theory like the “tradegy of the commons”

Jason, as I see the situation in retrospect, the financial liability of systems of personal injury compensation in Australia was being increasingly threatened in the 1980s and 1990s by the relatively large percentage of patients with long-term claims due to persistent pain and the resultant disability.

In response, state Governments enacted legislation to change the systems from their previous emphasis on disability in relation to employability to that of apparently medically-measurable impairment.

Persistent pain was then deemed not to be an impairment and therefore not compensable.

By contrast, psychological and psychiatric conditions became impairments and thereby attracted compensation.

This change left many of our patients “in limbo” and at the mercy of increasingly unsympathetic claims officers and their medical advisors who had become dependent upon them for their daily bread.

The industry of “independent medical examiners” has sprung up and is now increasingly under the control of multinational corporations.

Incidentally, I looked up the “tragedy of the commons” as I was unfamiliar with it.

I found it (on Wikipedia) to be a “term used in social science to describe a situation in a shared-resource system where individual users acting independently according to their own self-interest behave contrary to the common good of all users by depleting or spoiling that resource through their collective action.”