Guest writer, Emily Moore, on working with non-verbal children in pain: Working with children in pain can be a challenging and disheartening experience. On top of this, what if the child is unable to verbally tell you about their pain? And what if they only have a small list of predetermined words/pictures to describe all of their pain experiences? In part 1 of this blog, I will briefly introduce you to some augmentative and alternative (AAC) options and highlight the challenges that non-verbal children can face when trying to explain their pain. I think that some of these findings may generalise to verbal populations too, so please dive in! Part 2 of this blog will cover the potential stigma of pain thresholds in non-verbal kids, and discuss self-report versus proxy-report in our pain assessments.

Part 1 of 2: Reporting your pain, should not be a pain

Let me begin this journey with Marco – a fictional boy whose story is based on an amalgamation of patients I’ve seen.

Marco is a six-year-old boy with cerebral palsy (CP). He loves anything to do with Spider-Man, uses a walker to navigate around his house and school, and always gets excited to use his new red wheelchair for family outings. After a holiday with his family, his mother calls me to reassess his pain.

‘I am not sure what has happened, he just keeps pointing to his hips while crying,’ she reports. ‘He keeps selecting “pain” on his device, but I can’t see any cuts or bruises’.

Another fact about Marco? He is considered ‘non-verbal’.

As I arrive for his in-home physiotherapy appointment, I reflect on all the possible details that I may need to assess his pain. A thought comes into my head – has Marco ever tried to tell me about his pain before?

His mother hands me Marco’s communication device and pleads, ‘Please figure out what is wrong with him’.

I look down at this device and attempt to start unravelling Marco’s pain.

Getting the message across

How frustrating must this be for Marco? Typically, when someone feels pain, they can often alert others quickly and be heard ‘loud and clear’. But when a child is unable to speak, getting a message across can be slower, more fatiguing, and misinterpreted by others. Children who have limited speech are seen to have complex communication needs (CCN) – another way of saying ‘non-verbal’– and may need to use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) systems.

What is augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)?

Broadly, AAC is any form of communication strategy used to supplement or act as an alternative to spoken language (Battye, 2017). There are many forms of AAC, but they can be categorised into two subgroups – unaided and aided. Unaided AAC does not require the use of external ‘aides’ because it is communicated using your body, such as sign language, facial expressions, and vocalisations. In contrast, aided AAC uses external ‘aides’ which can range from low-tech communication boards/books to high-tech platforms and devices.

After seeing all the vocabulary and pictures in the high-tech option, you could be thinking: ‘Surely there are plenty of options to get all the information you need?’ Unfortunately, the answer is often ‘No’.

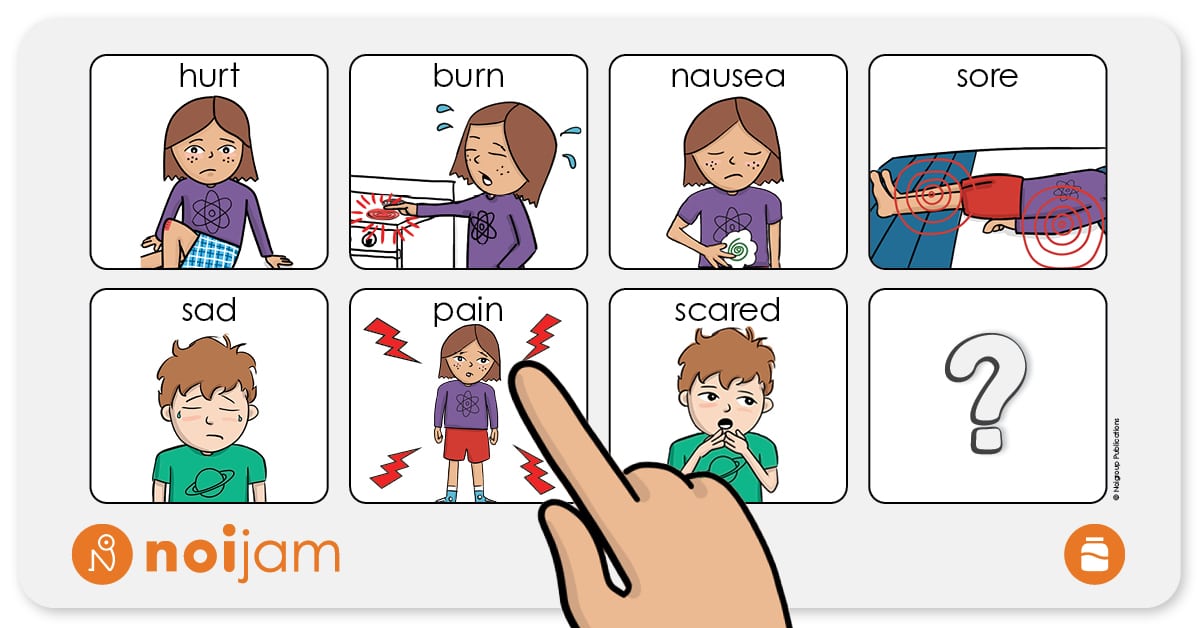

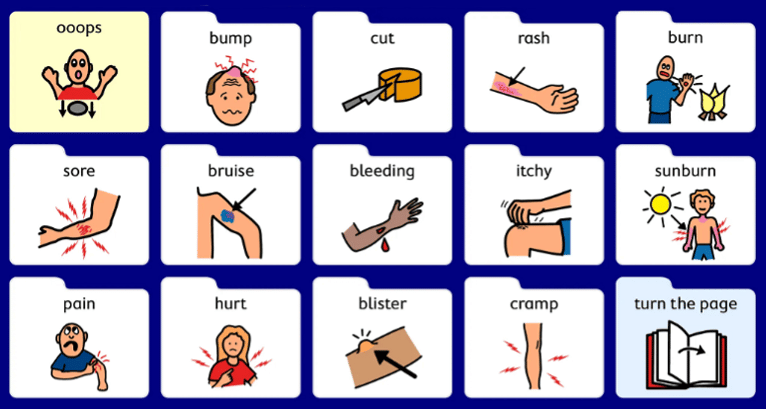

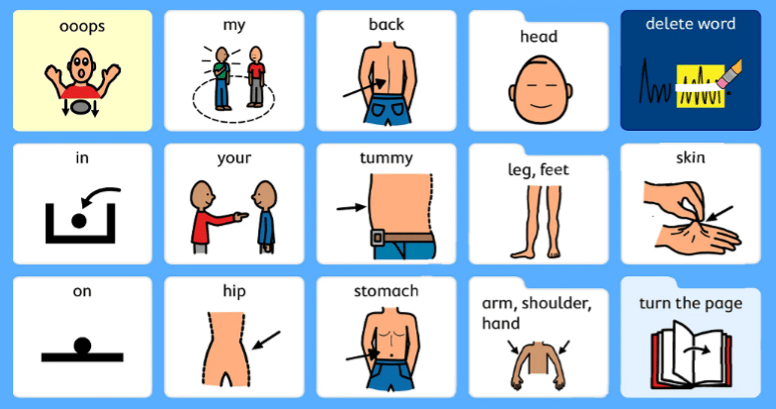

Reflect on the last time you had pain. If you were to turn to the person next to you and tell them what your pain is, where it is, the severity, and how you wish to manage that pain – I assume, that you could quickly and easily do so given that you are telling the person through oral speech. Now, let’s try and do this again, but this time you are only able to use these pictures:

|

|

|

How did you go? Did you get your message across?

For clinicians who work with children with CCN, it can be challenging to determine where a child may be experiencing pain, and even more challenging to determine what classification of pain it is, its severity – depth, duration, onset, 24-hour pattern and so forth. Children are also expected to navigate multiple steps and pages of potentially irrelevant options in order to answer our well-meaning questions. This process can be disheartening for the child and clinician alike. Pain is so much more complex and individualised than those simple words/pictures.

What if the child cannot tell us what they are experiencing?

What if their pain does not have a visible ‘cause’ or injury?

We know that pain can be elicited and influenced by many things that are not ‘visible’ (Read about these influences in Book 2 of Zoe & Zak’s Pain Hacks). Yet, most of the above pictures denote a visible cause or injury for the pain. If Marco had no ‘visible’ injury for his pain, he would already be stuck in telling me what was wrong. What a huge barrier! This significantly limits communication in the new era of pain sciences.

I can hear the questions now…

Well, why is this the case?

How can we help these kids to explain their pain?

What happened to Marco?!

Tune in to part 2, coming soon, to explore Marco’s story further.

– Emily Moore

BPsych (Hons), BPT (Hons)

PhD Candidate

IIMPACT in Health | Body in Mind (BiM) Research Group

University of South Australia | Kaurna Country

Email: emily.moore@mymail.unisa.edu.au

References

Battye, A. (2017). Who’s Afraid of AAC?: The UK Guide to Augmentative and Alternative Communication (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315172910

Want more?

Images from Zoe and Zak’s Pain Hacks, Book 3: Zoe and Zak’s Brainy Adventure! © Joshua W. Pate, Noigroup Publications (In press 2022)

comments