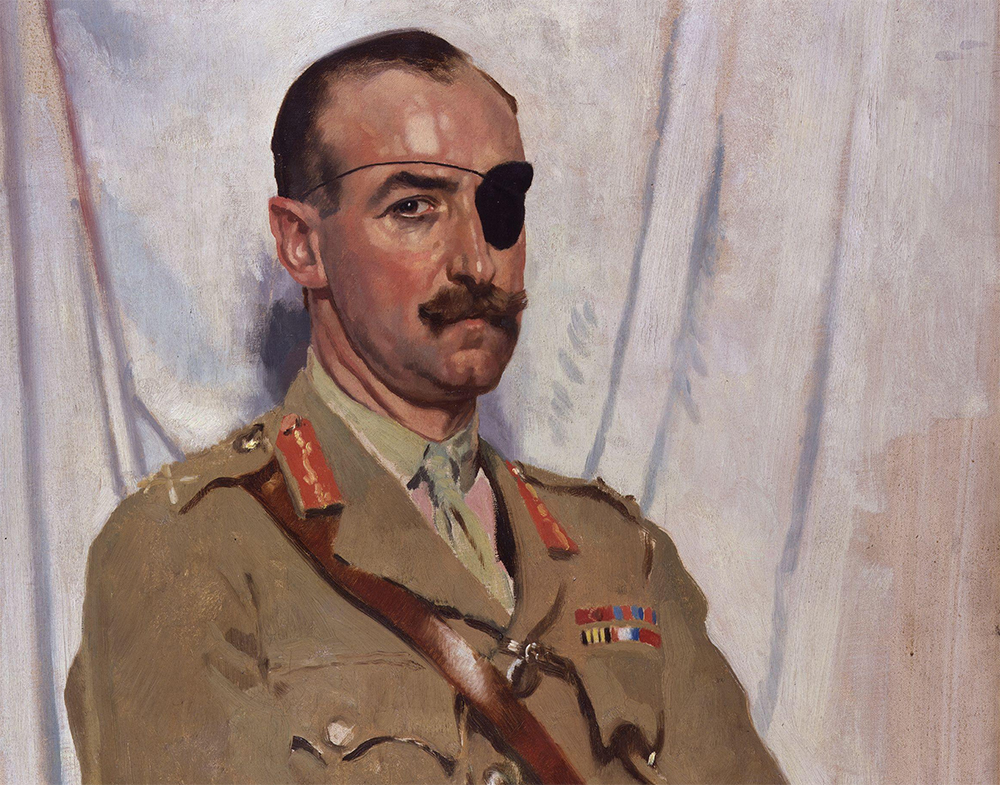

‘Happy Odysseys’, the remarkable memoirs of Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart (1880-1963), was first published in 1950 (with a forward by Winston Churchill no less). The BBC called him the “unkillable soldier” and some writers suggested his story was Wikipedia’s best.

De Wiart fought in wars for nearly 50 years including the Boer war, the first and second world wars and skirmishes in between.

He was shot in the groin and stomach in the Boer war, then in the face and twice in his left eye which was later removed and he also had part of his left ear shot off. In WW1 he was shot in the wrist forcing his watch into the wound. The hand was later amputated but not before he pulled off two of his fingers. (“I felt no pain doing so”, he said). He lost part of his skull and was shot in the ankle in the Somme. Numerous soldiers next to him were killed and he reported body parts flying around him. Infantry only lasted an average of a fortnight and in one fight he lost 8 new officers in an afternoon. Despite his officer status, he loved mixing it with soliders at the battle front. He would pull grenade pins out with his teeth and then lob the grenade with his one arm. De Weirt won a Victoria Cross and attributed it to his men. Later in the war, he was shot in the hip and the leg and the rest of his left ear was blasted off. Despite all this, he actually said he enjoyed the war!

Phew – I was already exhausted and there was another war to go!

He managed to get a gig in World War II, survived two plane crashes, many near misses, he was knocked unconscious a number of times, shot in the elbow and later imprisoned in a POW camp in Italy though he managed to dig himself out. Later he fell over and broke his back and during surgery, doctors took the opportunity to remove bits of shrapnel from previous skirmishes.

While not fighting, he managed to break his leg playing polo and crack his ribs in a horse fall. Did I mention that he also had a badly blistered toe – “it was agony”.

This is just a list of events – the injuries often involved months of hospitalisation, (his hospital in London kept his pyjamas for his next visit), repeated surgery and infections. In one incident, clothing got blasted into a hip wound and was septic for 3 months. Remember that this was pre-antibiotic days and the pain medications on offer were crude morphine, alcohol and tobacco (although loved ones could send heroin and cocaine packages).

So many questions

Increasingly as I read the book, I wanted to know more about this incredibly brave man, and not just his exploits and how good at sport his friends were but what was he thinking and feeling and how did he manage through this remarkable life. I thought – what an opportunity to teach us something about pain, coping and resilience and all sorts of things about life.

So I reread the book for clues but they were hard to find. The word pain is only mentioned 10 times in the book. He does not mention his wife and daughters and nor does he mention his Victoria Cross, preferring to discuss it as a team effort. De Wiart loved all things military from childhood and as a child confronted death when he came upon a suicide by gunshot –“I was haunted for many nights”.

The only two statements relating to how he experienced trauma are:

- On the boat trip back to England after being shot in the eye: “the journey was nothing less than a nightmare. I was practically blind, physically and morally the world was black and I was sick at heart”. When the eye was removed there was a chunk of metal in the socket.

- After the hand amputation (this was a bit by bit amputation initially): “While lying there, I was too exhausted and ill from pain to care whether I lived or died”. During this time he heard that his father had died but he makes no mention of the impact.

De Wiart dreaded January the 3rd, the date of his eye removal, and the date of his father’s financial crash. As he had been wounded 6 times on a Sunday, he avoided any new undertakings on a Sunday. He said that the worst memory of the wars was the smell of putrifying bodies, something that never left him.

More questions – how did he manage – the importance of balance in all our lives.

De Wiart’s life was a series of up and downs – huge ups and downs. “I have found life to be very well balanced and what she takes away from you with one hand, she often gives back with the other”. His downs were usually linked to injury and his ups related to promotions and new wars to fight. Is this just “getting on with it” as a coping strategy?

And he wrote this remarkable metaphor “People who enjoy life seldom have much fear of death and having taken the precaution to squeeze the lemon do not grudge throwing the rind away”. I wonder if de Wiart considered life to be sour like a lemon. I wonder what readers think of this lemon metaphor – for me, it is a faulty new car and it is a sour fruit.

He was a fitness fanatic and exercise clearly helped him cope. He also loved shooting game – I wonder whether this helped?

But maybe the writing style is just that of 70 years ago. Perhaps it is how men and women coped with the horrors of the time, being stoic, perhaps in denial. But what does it mean to our lives today and how we live them?

Maybe public denial of pain is helpful to some. Maybe he could see that his denial of pain would help his troops cope. Maybe he got a thrill out of this.

Maybe every war that he came out added to his belief that he would come out of the next one stronger – what doesn’t kill you will make you stronger .

And I wonder how his early life experiences were in establishing coping strategies in later life.

What an extraordinary story and human. I enjoyed the book, but I would have loved to be able to sit down with him and tease out more about his life. I think I would have learnt a lot.

– David Butler

But also in modern Western man, who have been lucky enough not to witness directly the terrible events of a battlefield, do we start to feel a loss, because we have not truly tested our mettle.That somehow we are not quite men, that mixed up in the degradation is a thrill and heightened sense of being that our very safe and comfortable lives can only guess at?.

Will my telling my grandchildren about my week long Vipassana silent retreat carry the same depth and myth building as previous generations stories of derring do?.Is this anything to do with our epidemic of chronic pain?.Perhaps a small piece of a jigsaw.

I do like the suggestion of the week long Vipassana silent retreat as a modern corollary of a shootout! There is a small piece of the jigsaw here – maybe testing our mettle takes us out of our comfort zone, out of the relentless need for approval and into new creative zones. We would conceptualise it as SIM hunting at NOI

Cheers

David

What a thought provoking read, thank you!

I wonder if it wasn’t stoicism or denial of pain so much as acceptance of pain as a part of the human condition and especially as a part of war. War is painful, for soldiers and civilians alike. I can’t imagine one could successfully be in denial of it when they’re in the midst of it.

I think we are more averse to pain now. We have notions that there should be no pain at all, that it must be fought and eradicated. And so we suffer for it. I think that is relatively new and only present in post-war societies. I wonder how those who still live in war torn and violent countries think about pain and suffering, I imagine there is some level of expectation that it is a part of life.

Pain, and suffering, has always been a part of the human condition. It is why I had to read literature as well as the science to help me make sense of things. Writers have always tried to tell the truth of the human experience. Reading Dickens and Tolstoy helped me understand what it means to be a complex human with existential questions, which pain readily thrusts upon, more so than just reading the science ever could.

And as for lemons. I love lemon cookies and tarts 🙂

Thanks Joletta,

Thinking about this, pain is/was probably accepted as part of war so it wasn’t written about.

Say you had a group of new workers doing an orientation day for work at a particular company – we should also tell them something along the lines of “pain, your normal, natural and powerful defender will show up now and then during your working life. Its OK, its telling you to change behaviour and you are not necessarily damaged etc etc.

David